( 2020) found anxiety (and especially intolerance of uncertainty, an underlying construct thought to lead to some of the principal symptoms of anxiety) was associated with demand avoidance behaviours in children when controlling for an autism diagnosis.

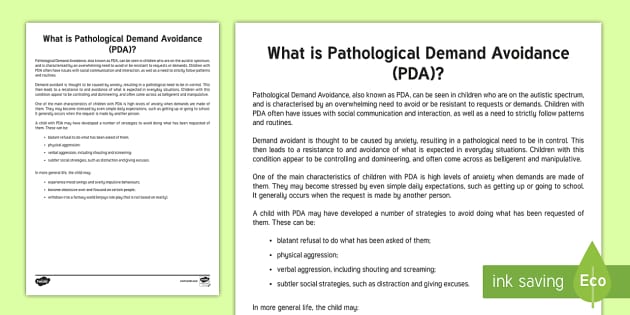

Avoidance may be initially localised to aversive demands, but then spread to, or ‘contaminate’ neutral or even positive tasks. Avoiding demands is itself likely to increase anxiety in the long-term, as found in research into procrastination (Abbasi & Alghamdi, 2015 for a review), thus setting up a self-perpetuating (and possibly amplifying) cycle of anxiety and avoidance. Adults with an EDA profile have reported high levels of anxiety (“My primary emotion is anxiety”), and experience a lack of control as catastrophic (“If I feel out of control everything goes very wrong, very quickly”, (Cat, 2018, p. EDA may therefore have some features in common with maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as eating disorders, selective mutism, and self-harm. This reinforces the use of avoidance behaviours in response to demands. In this framework, avoiding or delaying the imposed demand of an aversive activity enables a person to regain control of the situation, thereby reducing anxiety. Demand avoidance behaviours could be described as learned coping mechanisms, developed in response to extreme anxiety caused by an aversive stimulus. Indeed, some argue that demand avoidance may be described as a rational method of avoiding anxiety, especially for those with limited autonomy, such as children (Moore, 2020 Woods, 2019). Alternatively, as Woods ( 2019) argues, perhaps EDA is best described as a behaviour profile that can be seen across a variety of conditions (such as, potentially, conduct disorder and ADHD) or perhaps it can be attributed to (a combination of) already recognised conditions (Green et al., 2018).ĮDA is believed to be driven and maintained by anxiety (e.g. Persons with EDA are thought to have higher social fluency, engage in role play, and utilise socially strategic manipulative behaviour. Despite these overlaps, some practitioners and researchers suggest there are marked differences between EDA and autism which indicate that EDA is a separate condition (e.g. Demand avoidance could be a form of the ‘autistic inertia’ reported by some autistic individuals (Milton, 2019). Malik and Baird ( 2018) note the similarities between EDA and the restrictive repetitive behaviours of autism.

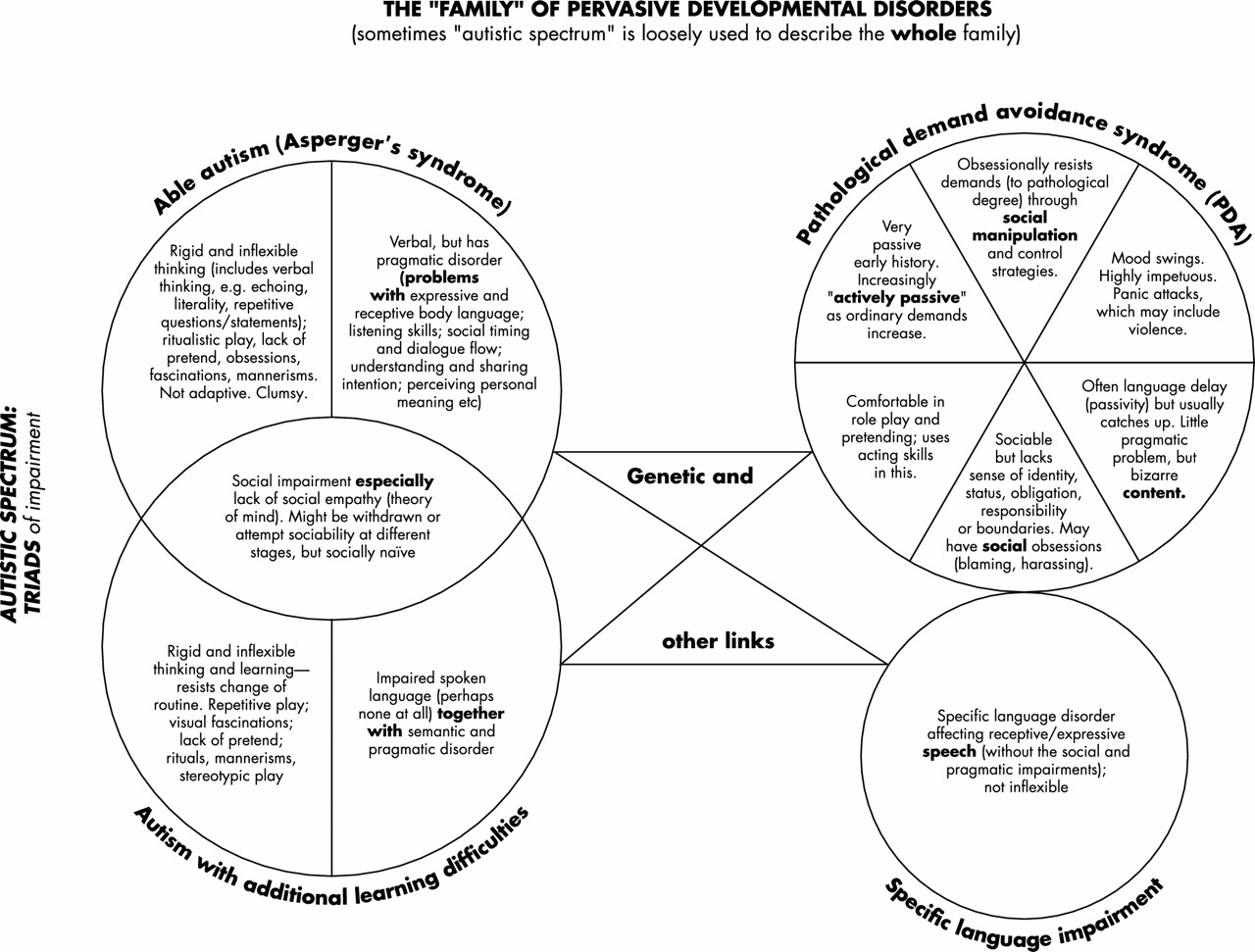

There are several overlaps between the descriptions of autism and EDA, such as social communication difficulties and a heightened need for control. Since autism is now so heterogeneous and the diagnostic criteria have broadened (Timimi & McCabe, 2016), many traits of EDA could potentially be attributed to autism (Kildahl et al., 2021). Currently, EDA is argued to be part of the autism spectrum, both by researchers and UK charity the PDA Society (PDA Society, 2020). Despite these characterisations, the most appropriate way of conceptualising EDA is debated.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)